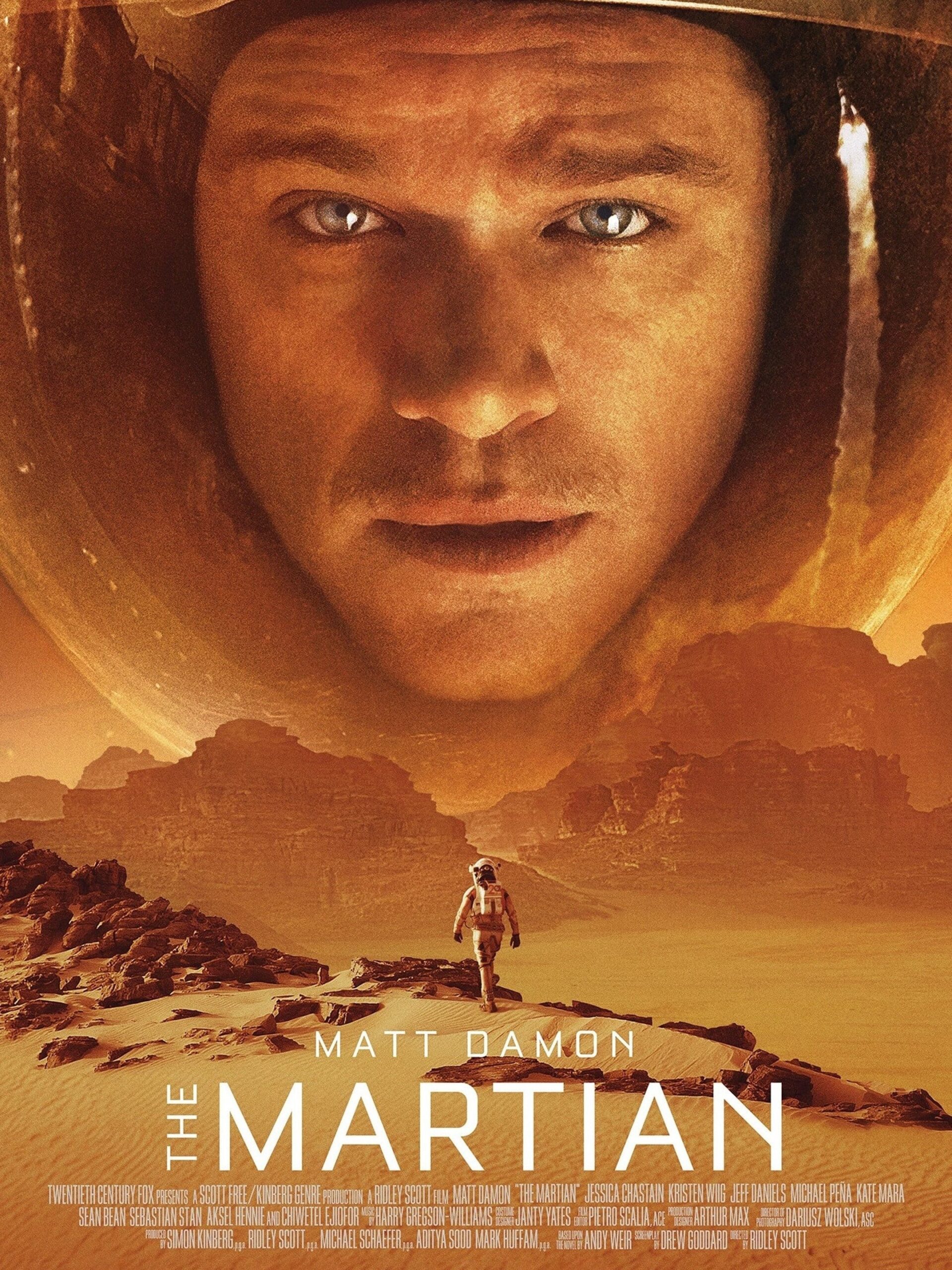

The Martian is a 2015 American science-fiction film directed by Ridley Scott, based on Andy Weir’s novel of the same name. Matt Damon stars as astronaut Mark Watney, who is mistakenly presumed dead and left behind on Mars. The film depicts his struggle to survive and the efforts of others to rescue him. While figuring out a solution, Mark Watney resides in a NASA-built ‘Hab’, where he uses his scientific and botanical expertise to make water and grow his own potatoes on Mars. Running low on food and left without any options after an accident in the Hab, Mark Watney eventually decides to undertake a desperate attempt to return to earth: he plans on driving a NASA rover to another part of Mars to take control of the Ares IV, a NASA lander that was sent to Mars in preparation for another mission.

The Martian is a 2015 American science-fiction film directed by Ridley Scott, based on Andy Weir’s novel of the same name. Matt Damon stars as astronaut Mark Watney, who is mistakenly presumed dead and left behind on Mars. The film depicts his struggle to survive and the efforts of others to rescue him. While figuring out a solution, Mark Watney resides in a NASA-built ‘Hab’, where he uses his scientific and botanical expertise to make water and grow his own potatoes on Mars. Running low on food and left without any options after an accident in the Hab, Mark Watney eventually decides to undertake a desperate attempt to return to earth: he plans on driving a NASA rover to another part of Mars to take control of the Ares IV, a NASA lander that was sent to Mars in preparation for another mission.

In the meantime, he considers the following:

“I’ve been thinking about laws on Mars. There’s an international treaty saying that no country can lay claim to anything that’s not on Earth. By another treaty if you’re not in any country’s territory, maritime law applies. So Mars is international waters. Now, NASA is an American non-military organization, it owns the Hab. But the second I walk outside I’m in international waters. So here’s the cool part. I’m about to leave for the Schiaparelli Crater where I’m going to commandeer the Ares IV lander. Nobody explicitly gave me permission to do this, and they can’t until on board the Ares IV. So I’m going to be taking a craft over in international waters without permission, which by definition… makes me a pirate. Mark Watney: Space Pirate.”

Mark Watney appears to be an excellent botanist, keeping himself alive on a distant planet without any support, but it remains to be seen if his legal knowledge is accurate. In this short essay, his train of thought is analyzed against the background of relevant international law in different steps. Three questions are answered: can a country claim territory in outer space? Does the law of the sea apply to actions on celestial bodies? And if the piracy regime would apply, would the actions of Mark Watney constitute piracy?

1. Can a country claim territory in outer space?

Watney correctly refers to the Outer Space Treaty (Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, boondockvapes including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies), introduced by the United Nations in 1967 and ratified by the United States. The treaty, which forms the general legal framework for all human activity in outer space, was stimulated by the United States and the Soviet Union, the two adversaries in the Cold War, to prevent colonialist land grabs from extending to outer space and to guarantee freedom of exploration and peaceful use. According to the main principles of space law, sovereignty and appropriation are prohibited in outer space and on all celestial bodies, including Mars. A quick example: just because Neil Armstrong planted an American flag on the Moon, does not mean that the US owns it. Likewise, if a state or a private entity lands on Mars and starts developing activities there, this does not imply any ownership or sovereignty.

Article 1 Outer Space Treaty

The exploration and use of outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development, and shall be the province of all mankind.

Outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall be free for exploration and use by all States without discrimination of any kind, on a basis of equality and in accordance with international law, and there shall be free access to all areas of celestial bodies.

There shall be freedom of scientific investigation in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, and States shall facilitate and encourage international cooperation in such investigation.

Article 2 Outer Space Treaty

Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.

These principles are echoed in the Moon Treaty (Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies), which also applies to other celestial bodies within the solar system:

Article 1, §1 Moon Treaty

The provisions of this Agreement relating to the moon shall also apply to other celestial bodies within the solar system, other than the earth, except in so far as specific legal norms enter into force with respect to any of these celestial bodies.

Article 11, §2 Moon Treaty

The Moon is not subject to national appropriation by any claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.

2. Does the law of the sea apply to actions on celestial bodies?

While the legal regime of outer space can in some aspects be compared to that of the high seas and the Outer Space Treaty states that no country can lay claim to any celestial body, as is the case for the high seas, that does not mean that the law of the sea necessarily applies. Though the Moon Treaty attempted to model space law on the law of the sea, that treaty can be considered a somewhat failed treaty, as only a handful of nations, none of which possess the ability to launch astronauts into space, have signed it. The United States, for one, are not a party to the Moon Treaty, so it is not directly relevant for Watney. As the Moon Treaty is not operational, could the law of the sea be applied instead? There are certainly some similarities in the legal status: celestial bodies and international waters are both considered ‘res communis’ and the deep seabed and the Moon share the qualification of ‘common heritage of mankind’. Supporting Mark Watney’s theory, one can claim that the Outer Space Treaty and the Moon Treaty, which explicitly mention that all activities in outer space shall be carried out in accordance with international law, implicitly refer to the law of the sea that governs a similar environment, but this line of thought should not be followed.

Article 3 Outer Space Treaty

States Parties to the Treaty shall carry on activities in the exploration and use of outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, in accordance with international law, including the Charter of the United Nations, in the interest of maintaining international peace and security and promoting international cooperation and understanding.

Article 2 Moon Treaty

All activities on the moon, including its exploration and use, shall be carried out in accordance with international law […].

Article 11, §1 Moon Treaty

The moon and its natural resources are the common heritage of mankind, which finds its expression in the provisions of this Agreement and in particular in paragraph 5 of this article.

The premise that the law of the sea applies on Mars seems to be based on the idea that the law in outer space is derivative from terrestrial international law with regard to areas outside the jurisdiction of states: if there is no space law, the law of the sea will do. This rash assumption is however incorrect: as a matter of fact, there is a body of space law entrenched within the United Nations’ Treaties and Principles on Outer Space. This consists of five UN treaties and five principles adopted by the General Assembly. As already mentioned, the main treaty regarding space law is the Outer Space Treaty. Surprisingly, this 1967 treaty predates the 1982 codification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Furthermore, UNCLOS says nothing about non-oceanic spaces beyond the limits of land. Even if there were a general ‘beyond any country’s territory’ article, it would in principle be superseded by the provisions of the Outer Space Treaty, which specifically regulate activities in outer space.

If the United Nations’ Treaties and Principles on Outer Space would still be force in the year 2035, when The Martian is set, there is thus a source of space law one should turn to before applying the law of the sea. But Watney’s argument, claiming that there are clear parallels between the status of the high seas in UNCLOS and that of outer space and celestial bodies in the Outer Space Treaty and the Moon Treaty, is indeed correct. Mars and international waters have a similar legal position, but this does not lead to the application of the law of the sea and the piracy regime of UNCLOS on the Red Planet.

3. If the piracy regime would apply, would the actions of Mark Watney constitute piracy?

If application of the piracy regime of UNCLOS would be deemed necessary because of the lack of specific provisions and rules in space law, the question still arises if the actions of Mark Watney can be qualified as piracy. Piracy is defined in UNCLOS as:

Article 101 UNCLOS

Piracy consists of any of the following acts:

(a) any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any act of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft, and directed:

(i) on the high seas, against another ship or aircraft, or against persons or property on board such ship or aircraft;

(ii) against a ship, aircraft, persons or property in a place outside the jurisdiction of any State;

(b) any act of voluntary participation in the operation of a ship or of an aircraft with knowledge of facts making it a pirate ship or aircraft;

(c) any act of inciting or of intentionally facilitating an act described in subparagraph (a) or (b).

Let’s start off with the elements that correspond to the piracy definition of article 101 UNCLOS. First of all, the territorial requirement seems to be fulfilled. Although the actions did not take place in international waters, repeating the earlier considerations regarding the application of UNCLOS on celestial bodies and outer space, Mars could alternatively be seen as ‘a place outside the jurisdiction of any State’. These broad, unspecific terms are generally believed to refer to Antarctica or uninhabited and undiscovered islands, but at first sight do not impede the application of the provision on Mars, which is not governed or controlled by any country. Also, the actions of Mark Watney are clearly committed for private ends, as his goal is to save his own life and return to planet Earth. Political or ideological motives are totally absent, so the requirement of private ends does not form an obstacle for his interesting line of thought.

Several other problems can however not be ignored:

- Taking the Ares IV cannot be qualified as an illegal act. By assisting him on how to operate the Ares IV and by making the appropriate calculations to get him home, it seems that NASA officials gave Mark Watney permission to use the lander. And even if this is disregarded and one assumes that NASA did not authorize him to take control of the Ares IV, the Outer Space Treaty clearly sets out a norm of mutual assistance and hospitality in outer space, which is echoed in the Moon Treaty:

Article 5 Outer Space Treaty

States Parties to the Treaty shall regard astronauts as envoys of mankind in outer space and shall render to them all possible assistance in the event of accident, distress, or emergency landing on the territory of another State Party or on the high sea […]. In carrying on activities in outer space and on celestial bodies, the astronauts of one State Party shall render all possible assistance to the astronauts of other States Parties […].

Article 12 Outer Space Treaty

All stations, installations, equipment and space vehicles on the moon and other celestial bodies shall be open to representatives of other States Parties to the Treaty on a basis of reciprocity. Such representatives shall give reasonable advance notice of a projected visit, in order that appropriate consultations may be held and that maximum precautions may be taken to assure safety and to avoid interference with normal operations in the facility to be visited.

Article 10 Moon Treaty

1. States Parties shall adopt all practicable measures to safeguard the life and health of persons on the moon. For this purpose they shall regard any person on the moon as an astronaut within the meaning of article V of the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies and as part of the personnel of a spacecraft within the meaning of the Agreement on the Rescue of Astronauts, the Return of Astronauts and the Return of Objects Launched into Outer Space.

2. States Parties shall offer shelter in their stations, installations, vehicles and other facilities to persons in distress on the moon.

Article 15, §1 Moon Treaty

Each State Party may assure itself that the activities of other States Parties in the exploration and use of the moon are compatible with the provisions of this Agreement. To this end, all space vehicles, equipment, facilities, stations and installations on the moon shall be open to other States Parties. Such States Parties shall give reasonable advance notice of a projected visit, in order that appropriate consultations may be held and that maximum precautions may be taken to assure safety and to avoid interference with normal operations in the facility to be visited […].

If any of the parties to the Outer Space Treaty owned the lander in question, they would have a hard time finding a sound legal argument for denying access in this specific situation. According to the specific provisions of the treaty, one ‘shall give reasonable advance notice of a projected visit’, but when someone is left for dead on an uninhabited, inhospitable planet, without efficient means of communication, it does not seem fair to harm his chances of survival on these grounds. As the Ares IV cannot be considered operational and the visit could therefore not interfere with its activities, it is debatable if this requirement is still in effect, and you could even claim that advance notice of the visit was given, as NASA officials were aware of his plans to travel to the Ares IV lander before he got there. It thus seems fair to assume that this situation constitutes an example of implicit permission.

As Watney and the Ares IV lander are both affiliated with the United States, one could perhaps argue that the ‘other States Parties’ aspect is not present and the mentioned provisions therefore do not apply, but common sense would suggest that if assistance and hospitality of other states is required, it should in any case be provided by the state of which the person in question bears the nationality. The assumption that the Ares IV lander belongs to the United States is however correct: the Outer Space Treaty provides that when a state launches an object into space, that state retains jurisdiction and control over such object while in outer space or on a celestial body. This principle is also stated in the Moon Treaty.

Article 8 Outer Space Treaty

A State Party to the Treaty on whose registry an object launched into outer space is carried shall retain jurisdiction and control over such object, and over any personnel thereof, while in outer space or on a celestial body. Ownership of objects launched into outer space, including objects landed or constructed on a celestial body, and of their component parts, is not affected by their presence in outer space or on a celestial body or by their return to the Earth […].

Article 12, §1 Moon Treaty

States Parties shall retain jurisdiction and control over their personnel, vehicles, equipment, facilities, stations and installations on the moon. The ownership of space vehicles, equipment, facilities, stations and installations shall not be affected by their presence on the moon.

According to these provisions, it clearly doesn’t matter that the Ares IV is unmanned, because it is still considered US property. This results in the conclusion that Mark Watney can hardly be seen as a pirate: he is a US government employee making use of US government property. Against this background, Mark Watney’s behavior is governed by his employment contract and the associated regulations: at most, he could be guilty of misconduct or unauthorized use of government property, which would leave him exposed to various disciplinary measures once he gets back to Earth, but these actions cannot be qualified as illegal, as a breach of his contractual obligations does not amount to breaking the law. In an attempt to hurdle this argument, it is claimed that Mark Watney’s cultivation of Martian soil makes him a planetary colonist and the very first ‘Martian’, erasing any relation with the United States, but this is of course in conflict with the main principles of space law regarding the prohibition of appropriation and state sovereignty: Mars constitutes a celestial body under the Outer Space Treaty and can thus not be colonized through settlement. Even if this reasoning would be followed, the qualification of Mark Watney’s actions as piracy would be prevented by the simple fact that this international crime requires an extraterritorial context, which would not be existent if Mars would fall under the sovereignty of a newly created state.

Apart from that, whatever crime Mark Watney could be guilty of by taking control of the Ares IV, he should be able to build an extremely strong case to justify his actions on the basis of the necessity theory. Necessity is accepted in the criminal law of many nations and provides that a crime can be excused if committing the criminal act was necessary to prevent greater harm to the defendant or others. Examples are ample: from speeding on the highway to get a person to a hospital in time to borrowing your neighbor’s garden hose without prior consent to put out a fire. If the situation qualifies as a real emergency, a person can be entitled to perform certain illegal actions that could help him (or others) out of dire straits, if he is not directly endangering others. The actions of Mark Watney probably meet all the requirements: there was no reasonable alternative, the harm he sought to avoid outweighed the danger of the prohibited conduct and he did not create or contribute to the emergency in the first place.

Furthermore, the Moon Treaty contains a specific provision concerning emergencies, which would be able to justify the actions of Mark Watney:

Article 12, §3 Moon Treaty

In the event of an emergency involving a threat to human life, States Parties may use the equipment, vehicles, installations, facilities or supplies of other States Parties on the moon. Prompt notification of such use shall be made to the Secretary-General of the United Nations or the State Party concerned.

- Taking control of the Ares IV cannot be qualified as an act of violence, detention or depredation. There are some questions concerning the accurate interpretation of the piracy definition of article 101 UNCLOS, but mere taking of a vessel does not seem to meet the requirements. If one finds a boat drifting out in the ocean and takes it without permission, this person does not necessarily qualify as a pirate, as he/she didn’t use any force or threat. Similar principles should apply here: the Ares IV is unmanned, so obviously no force or threat is required or used. Even if the Ares IV had belonged to another country (for example Russia or China), Mark Watney could probably take it without technically committing the international crime of piracy.

- Apart from the issues mentioned above, the actions of Mark Watney cannot be qualified as piracy because there were no two ships involved. First of all, it is highly debatable that the actions of Mark Watney to take over the Ares IV were initiated from the rover: he used the rover to get to the Schiaparelli Crater, where the Ares IV is located, but it is hard to conclude that the takeover was actually launched from this vehicle. Technically, it looks like he took over the Ares IV from the surface of the Schiaparelli Crater, which in international waters would correspond with a person taking control of a ship while swimming towards it, excluding qualification as piracy under article 101 UNCLOS. Secondly, the rover does not meet the requirements. UNCLOS does not offer an exact definition of a ship or aircraft, but one thing is certain: the ship of the person who commits the act of piracy cannot be a government ship, unless there is mutiny. In that case, crew members take control of the ship against the will of the government, causing the ship to lose its public character and virtually transforming it to a private ship. Leaving aside any possible discussion about the qualification of the rover and Ares IV as a ship or aircraft, the following can be concluded: as the Outer Space Treaty states that a state on whose registry an object launched into outer space shall retain jurisdiction and control over such object and Mark Watney did not perform an act of mutiny, the rover that Mark Watney used to get to the Ares IV would in any case be considered a government ship, which leads to the obvious non-fulfillment of the two ships requirement on multiple grounds.

- A last point, which is perhaps of lesser legal significance, is that the Outer Space Treaty’s qualification of an astronaut as an ‘envoy of mankind’ appears to be the exact opposite of an ‘enemy of mankind’ (‘hostis humani generis’), which is the historic designation for a pirate in international law. With that in mind, it thus seems contradictory to regard an astronaut as a ‘space pirate’.